What Is An Example Of A Country That Makes Use Of Another Nation's Currency?

Exchange Rates and their Measurement

Download the complete Explainer 220KBAn substitution rate is a relative toll of one currency expressed in terms of another currency (or group of currencies). For economies like Commonwealth of australia that actively engage in international merchandise, the exchange rate is an important economic variable. Changes in information technology impact economical activity, aggrandizement and the nation's balance of payments. (See Explainer: Exchange Rates and the Australian Economic system.) The Australian dollar is also the 5th most traded currency in strange exchange markets. There are unlike ways in which substitution rates are measured and, over the years, at that place have been different operational arrangements for determining the value of Australia's exchange rate.

Measuring Exchange Rates

Bilateral substitution rate

At that place are many means to measure an exchange rate. The most common way is to mensurate a bilateral exchange rate. A bilateral exchange rate refers to the value of one currency relative to another. Bilateral exchange rates are typically quoted against the Us dollar (USD), every bit it is the well-nigh traded currency globally. Looking at the Australian dollar (AUD), the AUD/USD exchange rate gives you the amount of United states of america dollars that you will receive for each Australian dollar that you convert. For example, an AUD/USD exchange charge per unit of 0.75 means that you will get US75 cents for every AUD1 that is converted to Us dollars.

Bilateral substitution rates are visible in our daily lives and widely reported in the media. Consumers are exposed to them when they travel overseas or when they order goods and services from other countries. Businesses are exposed to them when they purchase inputs to production from other countries and enter contracts to export their goods and services elsewhere.

Cross rates

Bilateral exchange rates also provide a basis for calculating 'cantankerous rates'. A cantankerous rate is an exchange rate calculated past reference to a third currency. For case, if the commutation charge per unit for the euro (EUR) against the US dollar is known likewise as for the Australian dollar confronting the US dollar, the exchange rate betwixt the euro and the Australian dollar (EUR/AUD) can be calculated past using the AUD/USD and EUR/USD rates (that is, EUR/AUD = EUR/USD 10 USD/AUD).

Trade-weighted index (TWI)

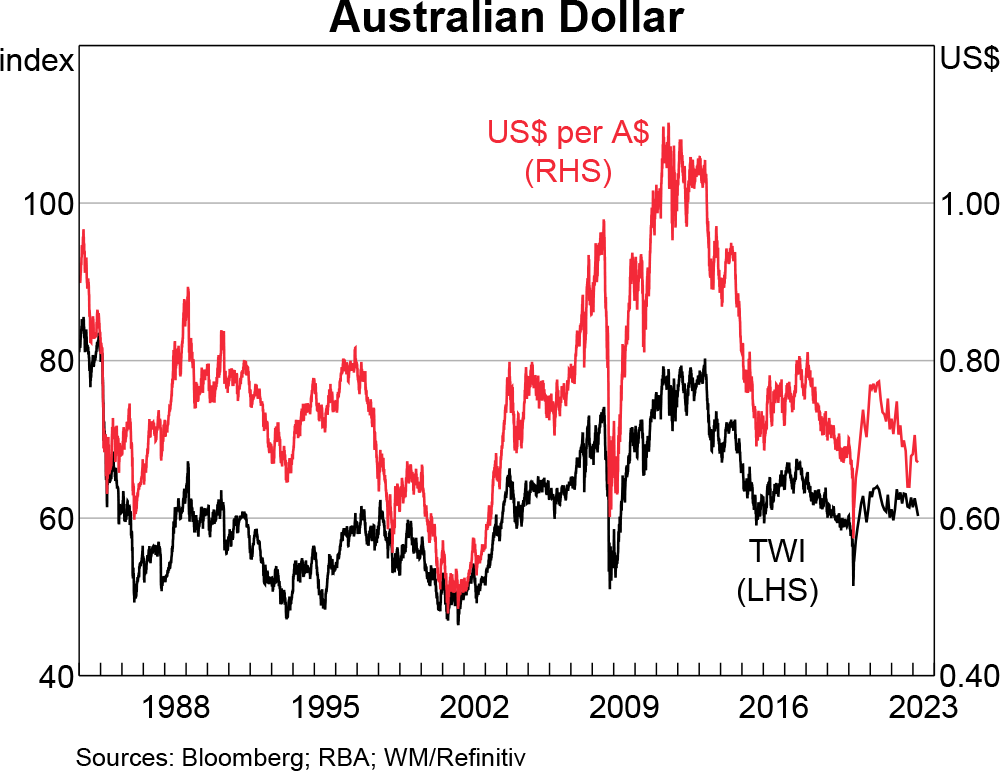

While bilateral exchange rates are the nearly ofttimes quoted exchange rates (and are most likely to exist quoted in the press), a trade-weighted index (TWI) provides a broader measure of general trends in a currency. This is because a TWI captures the toll of a domestic currency in terms of a weighted boilerplate of a grouping or 'basket' of currencies (rather than a single strange currency). The weights of each currency in the basket are generally based on the share of trade conducted with each of a country's trading partners (usually total trade shares, but import or export shares can also be used). As a result, a TWI can measure out whether a currency is appreciating or depreciating on average relative to its trading partners. A TWI generally fluctuates less than bilateral commutation rates considering movements in the bilateral exchange rates used to construct a TWI will often partly offset each other.

Australian Dollar

Exchange Rate Regimes

In that location are numerous exchange rate regimes a country may choose to operate under. At one terminate of the spectrum a currency is freely floating, and at the other finish it is fixed to another currency using a difficult peg. Beneath, we have divided this spectrum into ii broad categories – floating and pegged – although effectively distinctions tin can also be used within these categories.

Floating

Australia has had a floating exchange rate regime since 1983. This is a mutual blazon of substitution rate regime as it contributes to macroeconomic stability by cushioning economies from shocks and allowing monetary policy to be focussed on targeting domestic economic conditions. In a floating regime, exchange rates are by and large determined by the market forces of supply and demand for foreign commutation. For many years, floating commutation rates take been the regime used by the world's major currencies – that is, the US dollar, the euro area'due south euro, the Japanese yen and the UK pound sterling.

In the long term, the theory of purchasing power parity says that floating bilateral commutation rates should settle at a level that makes goods and services cost the same amount in both countries, although it is difficult to see this in the historical data. In the medium term, movements in an substitution charge per unit reflect things like changes in involvement rate differentials, international competitiveness and the relative economic outlook in each economy. On a daily basis, substitution charge per unit movements may reflect speculation or news and events that affect the respective economies.

A floating exchange rate can result in larger and more frequent fluctuations in the currency compared with pegged regimes. In a freely floating regime, the monetary authorization intervenes to affect the level of the exchange rate only on rare occasions if marketplace atmospheric condition are disorderly. In contrast, some floating regimes are more managed, and the monetary authority intervenes more than frequently to limit exchange rate volatility.

Pegged

Under a pegged regime (sometimes referred to as a stock-still regime), the budgetary authorization ties its official commutation rate to another nation'southward currency. In most cases, this will exist in the form of a currency target or target band at a rate confronting the Us dollar, the euro or a basket of currencies. The target provides a visible anchor and stability in the currency, although the target may move over time.

The budgetary authorization manages its exchange rate by intervening (buying and selling currency) in the foreign exchange market to minimise fluctuations and keep the currency shut to its target (or within its target band). A pegged commutation charge per unit regime limits monetary policy independence since information technology restricts the use of interest rates as a policy tool and requires the monetary authority to hold substantial foreign currency reserves for intervention purposes. (For a discussion of monetary policy implementation, please see Explainer: How the Reserve Depository financial institution Implements Budgetary Policy). An example of a pegged exchange rate is the Danish krone, which is pegged to the euro so that 1 euro equals 7.46 kroner, but can fluctuate between 7.29 and seven.62 kroner per euro.

What Is An Example Of A Country That Makes Use Of Another Nation's Currency?,

Source: https://www.rba.gov.au/education/resources/explainers/exchange-rates-and-their-measurement.html

Posted by: keaslereavelifire.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Is An Example Of A Country That Makes Use Of Another Nation's Currency?"

Post a Comment